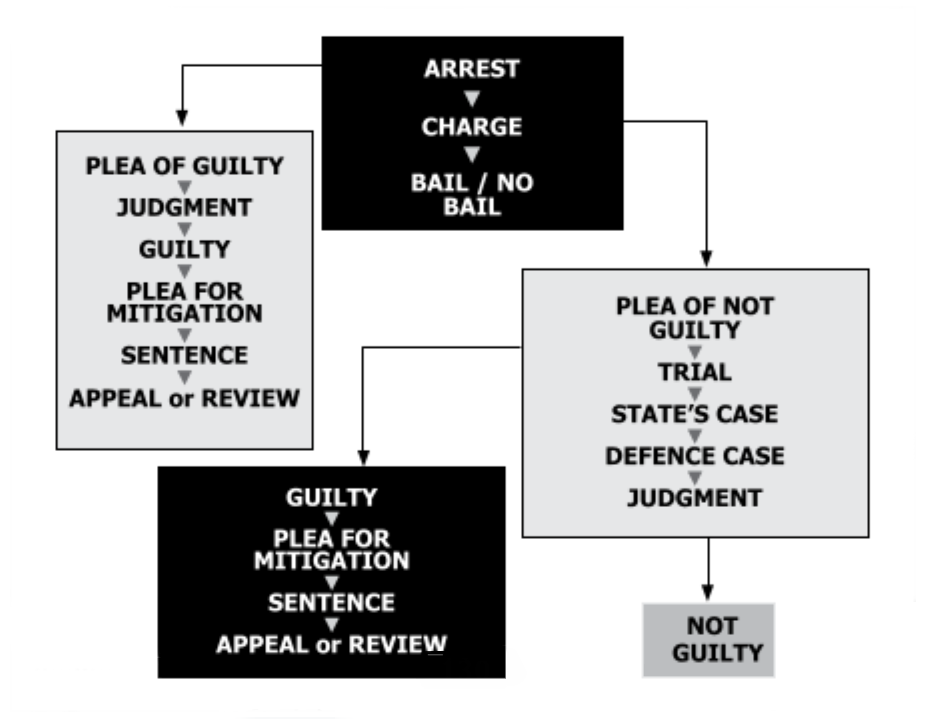

CHART: Summary of Steps in a Criminal Court Case

The first day

- To have time to find an attorney

- To prepare the case

- To contact witnesses

Before the criminal trial begins, you must appear in court and the prosecutor tells you what the charges are. The Magistrate will then ask, if you understand the charges, and whether or not you would like an attorney or if you would like Legal Aid to assist you. If you need an attorney you should ask for a postponement to enable you to get someone to represent you and prepare your case. The court should always ask you whether you want an attorney. You or the prosecutor can ask for a postponement if there are good reasons, for example:

So, on the first day in court you can ask for bail if you are under arrest and you can ask for a postponement of the case. You should also tell the magistrate if you were assaulted by the police or if the police put any pressure on you to make a statement.

The plea

Before the trial begins the Magistrate asks you to PLEAD. This means that he or she asks you to say whether you are ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’. Do not plead ‘guilty’ unless you are sure that:

- You did what the prosecutor says you have done AND

- You did not have a good reason to do what you have done.

You will plead ‘not guilty’ if:

- you did not commit the crime OR

- you did what people said you have done, BUT you had a good reason for doing it. This reason will then be used in your defence.

If you can prove a defence, the court may decide that you are not guilty of the crime you are charged with or that you are guilty, but that your reasons show you should get less punishment. These reasons are then called ‘mitigating factors’.

If you plead ‘guilty’ the magistrate will ask you some questions to be sure that you understand the charge. If your answers make the magistrate think that you have a defence, then the magistrate must change your plea to ‘not guilty’. If the magistrate accepts your plea of guilty, then she or he will decide that you are ‘guilty as charged’. There is no need for the trial to continue. Your next step will be ‘plea in mitigation’.

(See Evidence in mitigation)

If you plead ‘not guilty’ the magistrate must ask you more questions. This is to find out what your defence is.

The trial

The trial will go ahead if you plead ‘not guilty’ or the magistrate changes your plea to ‘not guilty’.

The state presents its case

The state prosecutor presents the state’s case to try to show that you are guilty.

The prosecutor calls witnesses for the state to give evidence against you. You or your attorney and the magistrate can also question each state witness. This is called cross-examination. The prosecutor can then question the witnesses again. This is called re-examination.

After the prosecutor has called all the state witnesses he or she closes the case. Now it is your turn (the accused) to present your case.

Discharge

If there is not enough evidence to show that you committed the crime you are accused of, then you can ask for a discharge. This means you ask the court to set you free. If the magistrate agrees then a discharge will be given. If the discharge is not given, the case will go on.

The case in your defence

The magistrate or judge will ask you or your attorney if you want to give evidence, and if you want to call witnesses. Sometimes it is not necessary for you to give evidence yourself but if you decide not to, the judge or magistrate might think that you are trying to hide something. All evidence is given under oath. After you have given evidence (if you choose to), you or your attorney can now call your own witnesses. Your witnesses are people who can give the court information to show that you are not guilty. The prosecutor and magistrate can then cross-examine each witness. You (or your attorney) can then re-examine each witness. After you or your attorney have called all the defence witnesses you ‘close the case’ for the defence.

Argument

The prosecutor then sums up the state’s case and gives reasons why you should be found guilty.

You or your attorney go over the main points of your defence, and summarise why the court must find you not guilty.

Judgment

After listening to both arguments, the magistrate or judge will say if the court finds you guilty or not guilty. The court may postpone the case to give the judge or magistrate time to think about the judgment.

You can only be found guilty of a crime if the state proves that you are guilty ‘BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT’. This means that there must be NO DOUBT in the court’s mind that you are guilty.

If the court finds you ‘not guilty’, then you are acquitted. This means you are free to go. If you paid any bail money, you can now ask to get it back.

Evidence in mitigation

If the court finds you ‘guilty’, then you get a chance to ask the court for a lighter sentence. This is called ‘evidence in mitigation’.

These are reasons that can help you to get a lighter sentence:

- If you are very sorry

- If you did something to correct the wrong, for example, if you gave back something you stole

- If you are younger than 18

- If it is your first offence

- If many people depend on you for support

- If you have other responsibilities, for example, a job

- If it can have a bad effect on you to be in prison, or to have a very heavy punishment, for example if you have health problems

Case Study

The Case of Sergeant Mandisi Mpengesi

The criminal court case of Sergeant Mandisi Mpengesi was heard in the Cape High Court. Sergeant Mpengesi was charged with the murder of his six year old daughter’s alleged rapist. He pleaded in mitigation that he had always been very committed to his police work, which involved helping people whose children had been molested and raped. He said he killed the man because of what this man had done to his daughter, and that he had only acted in a way any parent who loved his child would have done.

Sergeant Mpengesi was sentenced to 9 years imprisonment. There was an outcry from the public who thought that there were strong mitigating factors which should have helped him get a lighter sentence.

Sentence is given

The magistrate or judge will now say what your punishment (or sentence) will be. It can be:

- A prison term

- A fine

- A community service order

- Any of these together

- A caution and discharge

- For children under 18, the sentence can be admittance to a reformatory; or the passing of sentence can be postponed until the person turns 18

- Correctional supervision: this means serving your sentence outside prison under the supervision of a ‘correctional official’

Minimum sentences – The Criminal Law Amendment Act lays down harsh, and minimum, sentences for people who would previously have received the death sentence. The court has to give you at least the sentence laid out in the Act for the specified offences.

Maximum sentences – If a law says that the maximum punishment for a particular crime is 6 months or R600, the court does not have to sentence you to these maximum amounts. The sentence can be anything up to these maximum amounts.

Alternative sentences – If you are found guilty the court might sentence you to a fine OR imprisonment. So sentences can be given ‘in the alternative’.

Suspended sentences – The court may sentence you to a period in prison but suspend all or part of the sentence. This means that the court says you will not be punished on condition that you do not commit a similar crime over a certain period of time. The court gives you a chance to show that you will not do the same thing again. For example, the court may sentence you to 1 year in prison but suspend this sentence for 3 years. This means that you do not have to go to prison now, but if you are found guilty of committing the same or a similar crime in the next 3 years then you will have to go to prison to serve your sentence of 1 year.

You will also get an additional sentence for the new crime you committed.

You are found guilty of ordinary assault and sentenced to 3 years in prison. Two of these years are suspended for 5 years. So you serve 1 year in prison. After that you are released. Your sentence is suspended for the next 4 years.

If you are charged and found guilty of assault in the next 4 years then you will have to go to prison to serve out the rest of the first sentence which is another 2 years. This will be in addition to the new sentence you might get for the second assault.

Review or appeal

You can ask for permission to appeal against the decision of the judge or magistrate if you don’t agree with the judgment. You can also ask for a review if you think there were any irregularities during the trial.(See: Trials, appeals and reviews)

Get assistance with: